How do you run a digital transformation in a newsroom?

11 Sep 2023

Written by Joanna Kocik, content specialist at Autentika

We talk to Rafał Mrówka, a professor at SGH Warsaw School of Economics, about the digital transformation in media companies and explore innovation managers' challenges in the digital age.

Rafał Mrówka is a professor at SGH Warsaw School of Economics, director of the MBA-SGH and MBA for Startups programmes, digital transformation and leadership expert, management consultant and coach with over 20 years of experience, specialising in researching and building employee engagement.

Joanna Kocik, Autentika: Let’s imagine I am an Innovation Manager in a media company facing a digital transformation process. What challenges await me, and what will I be confronted with when I initiate significant organisational changes?

Rafał Mrówka, Ph.D.: Let's start by assuming we know what we want to achieve. It is not enough to acknowledge the need for change; we must also have a vision of what that change should look like – and that’s your task as a leader. Of course, a vision is only the first step in the process and does not guarantee success.

The biggest challenge is to convince the people affected by the change because even if they are aware of the inadequacies of the current system, they may cling to their old ways and habits. That’s why the leader’s first task is to convince people that they should fear the status quo more than change.

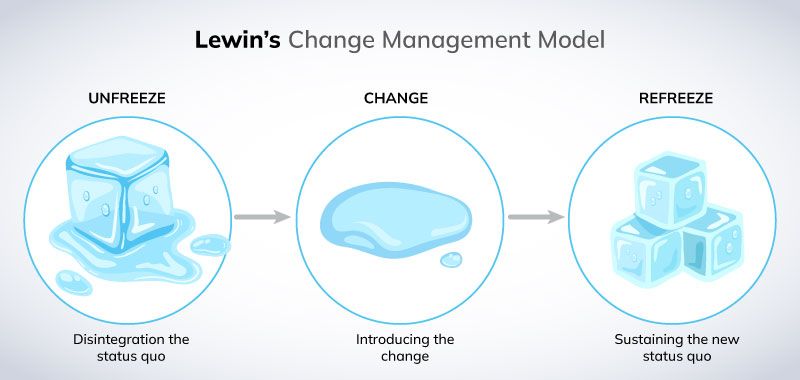

This process can be compared to Kurt Lewin’s model of change, which consists of three stages (unfreeze, change, refreeze). The first stage, unfreeze, aims to make people realise that change is necessary and attractive. Still, not everyone will be convinced immediately – some people are naturally innovative and adapt quickly, while others need more time and effort. To bring about meaningful change, the leader must convince the early adopters and make them discover the attractiveness of change (and understand the risks associated with maintaining the status quo).

Read also: How to clean up a back-office system at an online media giant? Case study

Kurt Lewin's model of change consists of three stages: unfreeze, change, and refreeze.

What’s crucial is that change will not happen at once but in stages – and success in these early stages can be a powerful argument for the right direction. Quick wins, carefully planned by the leader, can help convince the undecided that they are on the right path.

In this context, it's important to recognise that a change leader seldom operates in isolation. Instead, they often must collaborate with various stakeholders to drive transformation and sometimes convince them of the necessity of this change and the financial investment it requires.

Then, how does a change leader navigate the process of persuading and aligning stakeholders within the company, considering the presence of higher-ups like the CFO and the board of directors? Could you shed light on the potential obstacles and strategies involved in ensuring that change isn't delayed?

To effectively navigate these challenges, the first step is to secure the support of influential people in the organisation. Initiating significant change without the backing of top management is often an uphill battle, so convincing these leaders of the necessity of change is usually the first hurdle to overcome. Without their buy-in, progress can stall as they significantly influence whether or not the changes are implemented.

The strategy may be to start at the top and convince the most senior executive to endorse the change. If these key decision-makers are open to the idea, building momentum from this point may be beneficial. Another approach might be to assemble a coalition of middle managers who support the change. This coalition can then collectively approach the top-level decision-makers to get their endorsement. The choice between these strategies may depend on the culture and dynamics of the organisation.

A valuable exercise is to create a stakeholder map for change, identifying potential allies and adversaries (image generated by Midjourney)

A valuable exercise is to create a stakeholder map for change. This involves identifying potential allies and understanding why they might support the change. At the same time, it's crucial to identify potential adversaries and develop strategies to mitigate their influence. Some people in the organisation will inevitably resist change, possibly because of personal interests or concerns about their role in the face of new technologies or processes. When faced with such resistance, the leader should consider arguments and solutions to address their concerns.

Complete unanimity within the organisation is often unrealistic, but the key is to have a more “direct line” to the most influential figures. This process requires a deep understanding of corporate politics, negotiation skills and effective communication throughout the different phases of the change initiative. We’re talking about organisational diplomacy – but here, everything depends on the dynamics and conditions of the organisation.

Read also: 7 lessons I have learned about digital transformation in newsrooms

Let me illustrate this with an example: We have a Director of Innovation who is explicitly hired for this role, and eager to take action. Initially, they secured permission to conduct an external audit of the existing tools. As expected, the audit yielded unfavourable results, indicating a significant overhaul needed to achieve the company's KPIs and business objectives. How can a leader in this position push through the necessary changes?

Several aspects of this scenario need to be addressed. The first element is the diagnosis itself. The fact that an external entity conducted an objective diagnosis and found unfavourable results can be beneficial because it signals a real need for change. Ideally, the audit should not only diagnose the situation but also highlight the severity of the current condition and the risks and potential consequences of maintaining the status quo. This can help to create a sense of urgency among stakeholders within the organisation.

Given a limited budget, which is almost always the case, a leader must also think strategically about where to initiate change (image generated by Midjourney).

In addition, it is beneficial to consider organisational dynamics. In organisational theory, it is assumed that the goals and interests of different groups and departments in an organisation often diverge. This political reality means different groups prioritise their claims over those of the organisation. Against this unfavourable scrutiny, the change leader should develop a narrative demonstrating how the proposed changes will benefit the organisation and specific groups or groupings within it. This strategy may involve pitting different groups within the organisation against each other to gain support for the change.

Given a limited budget, which is almost always the case, a leader must also think strategically about where to initiate change. Instead of immediately undertaking a complete restructuring, it’s better to start with a pilot project – select a department or area where the change can be implemented relatively quickly and cost-effectively. If the pilot project succeeds (quick win), it can be a powerful persuader for further actions, especially when people or departments directly affected by the pilot become advocates of the change. Their positive experiences can give more credibility to the initiative.

In your experience, is it common for organisations to commission external audits to assess their tools and systems? When such audits are carried out, are the results usually expected to be unfavourable, or are organisations sometimes surprised by the dire situation?

Organisations typically don't engage an external company to showcase their operations' excellence. Instead, the aim is to pinpoint areas in need of improvement. Therefore, it is natural to anticipate that the audit results may reveal shortcomings and inefficiencies. But it does not exclude the “surprise effect” – and let me explain why.

People inside the organisation are often used to the quirks of working with an inefficient system. Over time, this familiarity can lead them to believe that the system is not as bad as it may seem to outsiders. Then, when an external audit comes along and declares the system dramatically inadequate, it may be met with scepticism. After all, staff may wonder how such an inefficient system could have lasted so long if it was as problematic as the audit suggests.

This surprised reaction is quite typical. In my experience as a consultant, I have encountered this reaction repeatedly when conducting audits. In most cases, people are genuinely surprised by the audit results and how different they are from their internal perceptions. But this element of surprise often catalyses change, prompting companies to address issues they might not otherwise have identified.

Read also: 6 barriers to collaborative and innovative newsroom culture

This surprised reaction to an audit is quite typical, but this often catalyses change, prompting companies to address issues they might not otherwise have identified (image generated by Midjourney).

A question that came to my mind is: who’s the real beneficiary of the change? Should our leader demonstrate that a change benefits users – journalists, and editors? Or should they focus on the business benefits? How do we weigh and decide what is more important?

The business benefit is obvious – we don't make changes for the sake of change. We make changes because they are meant to improve the current state. That means we also have to be aware that every change is followed by an inevitable slump, and it takes time to get on the growth curve and achieve improvement.

On the other hand, I think many managers make the mistake of viewing change only through the prism of results for the end customer or user. The political theory of organisation says nothing about customers; what matters are the groups within the organisation. Of course, we need to be aware that there is a customer or a user at the end to whom we want to give a new value.

Do these groups involve people other than C-level executives, for example, IT or HR departments?

Of course. Given the multifaceted nature of digital transformation, collaboration and alignment with various departments are essential for success. I cannot imagine digital transformation without individuals and departments with deep digital expertise, as these experts understand the intricacies of digital technologies and how they can be harnessed to drive organisational change effectively.

However, digital transformation is not just about technology. Equally important are people who excel at interpersonal communication. Change involves people, and without the ability to connect with and effectively support employees, digital transformation can face significant obstacles.

We also need people who understand customers and their needs – so I want to reiterate that a leader in this game needs to be a diplomat, bridging the different spheres, engaging in different conversations, and always keeping the overarching vision and goals in mind.

It’s obvious that communication is crucial here – but what are the golden rules for communicating change?

My golden rule is to communicate more rather than less. And that, in my opinion, is exactly the opposite of what many organisations do today. They think it is better to say less and that “people will figure out the rest”, which is wrong. In such a case, there can be resistance (or even rebellion) that destroys the change. So, I believe it pays to communicate change sooner rather than later, more rather than less, and to communicate even difficult things. It would be naïve to think that digital transformation will make everyone happy and that no one will be fired.

If a digital transformation means job losses, it is better to communicate this honestly and help those most at risk. It’s also a good idea to explain what might happen if the change does not happen – for example, we will have to lay off even more people. This can be difficult, especially if we have strong labour unions in the organisation. Good communication can help us get them on our side and get them to support change – even if it leads to redundancies. The key is to make people aware of the risks of not embracing change.

Not an easy task, I must say.

Yes, but we wouldn’t need transformation leaders if transformations were easy. That is their role and task – to do impossible things.

Do you want to initiate change in your organisation and look for a trusted partner in the digital transformation? See our offer for media